BIODIVERSITY:

The Nature of Investing

WRITTEN BY

Heather Ridill, CFA

Global Credit Portfolio Manager

The phrase “carbon emissions” was once confined to environmental science circles. Now it is common parlance in corporate boardrooms—priced, accounted for and traded.

Biodiversity, a word only first used in 1985, is on a similar path of heightened awareness, valuation and studied implications. However, unlike carbon emissions, the dimensions of biodiversity make understanding and potentially accounting for it more onerous.

Biodiversity is a broad topic with first and second derivative consequences. This paper is intended as an introduction to what countries and corporations are facing when it comes to biodiversity implications. In a follow-up paper, we will address biodiversity from an investor’s view.

Why Biodiversity Matters

Biodiversity refers to the variety of living species on Earth; it encompasses plants, animals, bacteria and fungi, including diversity within species, between species and of ecosystems.1 It provides economic value to the world as the source of food, medicines, fibers, fuels, industrial products and recreation through the four key ecosystem services (see below). While there are a multitude of estimates, the bottom line is that the value of nature is significantly material to the economy. The destruction of biodiversity can have a global financial impact.

ECOSYSTEM SERVICES

Source: Loomis Sayles.

VALUATION

Leading academic research on ecosystem services in 2011 (most recent data available) put its total annual value at $124.8 trillion.2,3 This figure is an estimate for the value of all ecosystem services, many of which are hard to put a monetary value on like air quality, soil formation and pollination. Additionally, natural assets play a critical role in the global economy. According to the World Economic Forum (2020), more than fifty percent of the world’s GDP is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services. Nature’s contribution to the global economy is estimated to be $44 trillion of economic value generated per year.4 To put these two values in context, global GDP in 2022 was $101 trillion.

While a complete collapse might be unlikely, especially over a short- to medium-term horizon, any decline of biodiversity presents rising physical and transition risks to the financial system. Additionally, over time we may see a higher correlation between biodiversity and financial performance driven by technical factors. This could include increased market scrutiny and significant focus on the financial materiality of biodiversity factors.

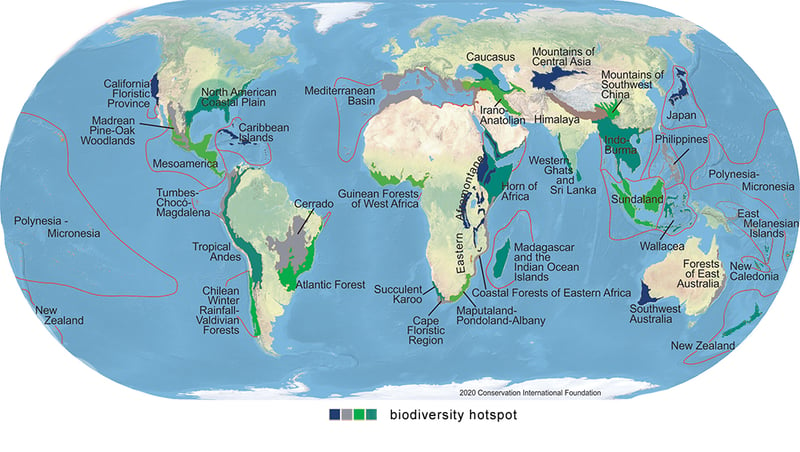

IMPORTANCE OF LOCATION

Biodiversity is not evenly distributed globally. There are currently 36 hotspots, which now represent just 2.3% of the world’s land area. These hotspots initially covered 15.9% of Earth but habitat destruction has led to this depletion.5

Many biodiversity hotspots are located in emerging markets (EM), elevating potential risks in these countries. Additionally, EM economies tend to be more reliant on ecosystem services, such as agriculture, forestry, fisheries and commodities.

GLOBAL BIOLOGICAL HOTSPOTS

Source: 2020 Conservation International Foundation. Legend colors distinguish adjacent hotspots.

Source: 2020 Conservation International Foundation. Legend colors distinguish adjacent hotspots.

SOVEREIGN SENSITIVITY

Currently, credit rating agencies do not explicitly take biodiversity and nature-related risks into account. But these risks could have significant impacts on sovereign creditworthiness, default probability and the cost of capital, which also has implications for companies in those countries.6

In general, analysts project global deterioration of ecosystem services over time. This implies negative rating trajectories that corporations and countries would be wise to consider.

If a country were to face a partial ecosystem collapse, its debt spreads would likely widen—especially for those facing significant default risk and higher funding costs. In turn, corporations doing business there would face higher borrowing costs and wider spreads on the back of country pressures. Additionally, we believe there would be potential for broad global economic and sentiment implications that could drive a repricing across regions.

While developed markets (DM) may have fewer physical risk concerns, they have significant ecological footprints due to their trade with emerging countries. The strain that DM trade can place on resources in emerging countries that may have more fragile biodiversity has prompted calls similar to the “fair share” discussion in climate change.7

CORPORATE VULNERABILITIES

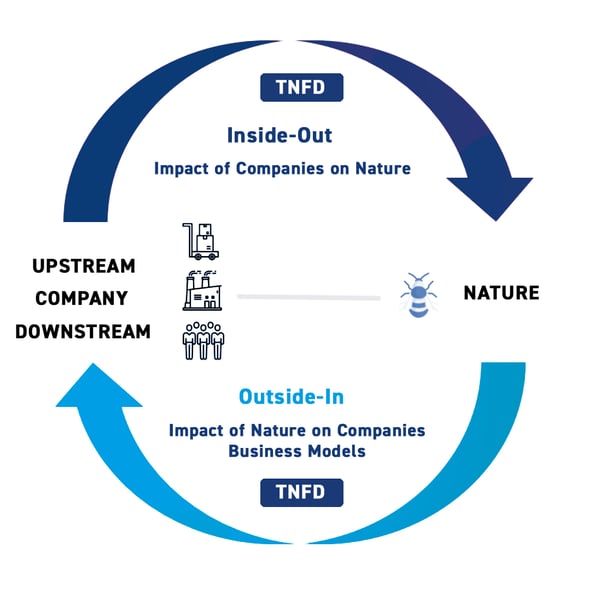

Unlike carbon emissions, where only the impact from companies is measured, biodiversity encompasses a concept called double materiality—an entity’s impact on natural resources and its dependency on natural resources.

Double materiality is a relatively new concept in financial reporting. To date, the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) has recommended entities report only their dependencies.8 We expect double materiality will be a key aspect of the Task Force on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD)’s final framework, expected in September 2023.

Source: https://kpmg.com/nl/en/home/insights/2021/11/its-time-to-act-on-nature-related-risk.html

Source: https://kpmg.com/nl/en/home/insights/2021/11/its-time-to-act-on-nature-related-risk.html

There are three primary categories of sources of nature-related financial risks that countries and subsequently corporations operating there face:

PHYSICAL RISKS

Natural systems compromised acutely (e.g., extreme weather) or chronically (e.g., degradation of soil or air quality).

TRANSITION RISKS

Misalignment of a company strategy with changing regulatory and policy situations.

SYSTEMIC RISKS

Complete system failure, including ecosystem collapse, aggregate risk of transition and physical risk and contagion of financial instability.9

Industries With the Most Material Dependencies and Impacts

The UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Center developed a methodology to determine which sectors have the most potential dependencies and impacts on biodiversity, and are “high priority” for consideration.10

The research determined the following top industries from a dependency and impact perspective. This goes to materiality – for these industries, there is a higher risk of materiality. Certain industries are highly dependent on nature for their key raw materials. An ecosystem collapse could be an existential threat to such sectors. Industries that have a high impact on nature are more likely to contribute to that collapse.

|

PRIORITY SUB-INDUSTRIES FROM A DEPENDENCY PERSPECTIVE |

PRIORITY SUB-INDUSTRIES FROM AN IMPACT PERSPECTIVE |

| Agricultural products | Agricultural products |

| Apparel, accessories and luxury goods | Distribution |

| Brewers | Mining |

| Electric utilities | Oil and gas exploration and production |

| Independent power producers and energy | Oil and gas transportation |

| Distillers, forest products and water utilities were also determined to have high potential dependencies but were removed due to low financial flows (i.e., index weights) versus other industries | Airport services, marine ports and services, and oil and gas drilling were also determined to have high potential dependencies but were removed due to low financial flows versus other industries (UNEP-WCMC, 2020) |

Up Next: Biodiversity From an Investor's View

The evolution of analyzing biodiversity implications for countries or corporations is in its early days. So where does that leave global bond investors? How do global bond investors gauge risk and value? Our next biodiversity paper will address these questions and provide an overview of insightful research considerations.

Author

Heather Ridill, CFA

Global Credit Portfolio Manager

Endnotes

1 https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/biodiversity/

2 Ecosystem services are the benefits people obtain from nature.

3 Costanza, R., de Groot, R., Sutton, P., van der Ploeg, S., Anderson, S. J., Kubiszewski, I., Turner, R. K. (2014). Changes in the Global Value of Ecosystem Services. Global Environmental Change-Human and Policy Dimensions, Elsevier.

4 Johnson, J.A., Ruta, G., Baldos, U., Cervigni, R., Chonabayashi, S., Corong, E., Gavryliuk, O., Gerber, J., Hertel, T., Nootenboom, C., & Polasky, S. (2021). The Economic Case for Nature. The World Bank.

5 Zachos, F.E., & Habel, J.C. (2011). Biodiversity Hotspots: Distribution and Protection of Conservation Priority Areas. Springer.

6 Agarwala, M., Burke, M., Klusak, P., Kraemer, M., & Volz, U. (2022). Nature Loss and Sovereign Credit Ratings. Bennett Institute for Public Policy Cambridge.

7 Fair share in the climate change arena is the concept that certain countries contribute more than others to climate change and some of them have greater resources to fight climate change. These countries have a larger responsibility to fight climate change.

8 The Financial Stability Board (FSB) is an international body that monitors and makes recommendations about the global financial system. It created the Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), which released recommendations that include a framework for companies and other organizations to develop more effective climate-related financial disclosures through their existing reporting processes.

9 KPMG. (2022). Introducing the TNFD Beta Framework: What boards and executives should know about nature-related risks and opportunities. KPMG.

10 UNEP’s primary source was the ENCORE tool. The methodology followed three steps – 1) determining what makes a production process high priority in terms of potential dependencies and impacts on biodiversity, 2) determining materiality of dependencies on ecosystem services and impacts on biodiversity, and 3) aggregating the highest rank for both impacts and dependencies and cross referencing with the importance to financial indices as a proxy for financial flows. (UNEP-WCMC, 2020)

Disclosure

This paper is provided for informational purposes only and should not be construed as investment advice. Opinions or forecasts contained herein reflect the subjective judgments and assumptions of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the views of Loomis, Sayles & Company, L.P. Other industry analysts and investment personnel may have different views and opinions. Investment recommendations may be inconsistent with these opinions. There is no assurance that developments will transpire as forecasted, and actual results will be different. Data and analysis does not represent the actual or expected future performance of any investment product. We believe the information, including that obtained from outside sources, to be correct, but we cannot guarantee its accuracy. The information is subject to change at any time without notice.

Any investment that has the possibility for profits also has the possibility of losses, including the loss of principal.

Market conditions are extremely fluid and change frequently.

Past performance is no guarantee of, and not necessarily indicative of, future results.

LS Loomis | Sayles is a trademark of Loomis, Sayles & Company, L.P. registered in the US Patent and Trademark Office

MALR031472